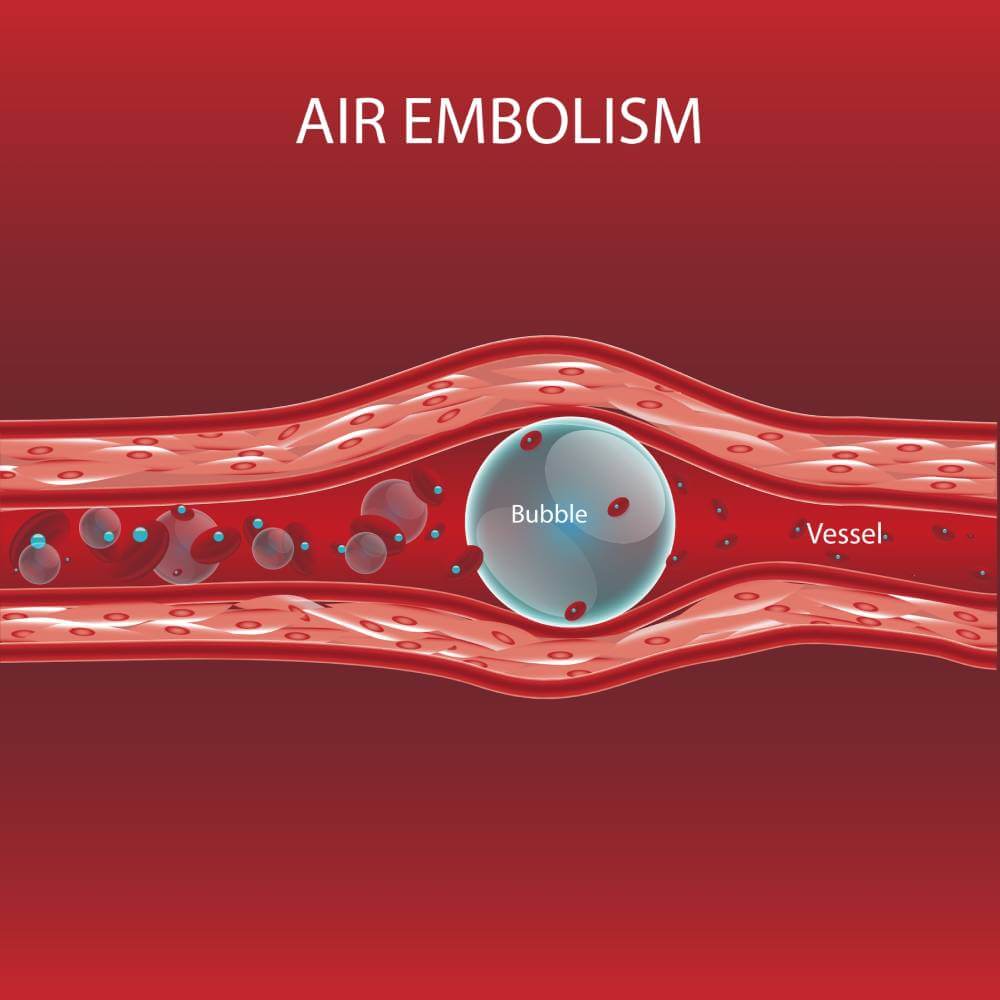

Gas or air embolism is a rare but dangerous and sometimes fatal complication of invasive procedures. It is caused when air is introduced to the intravascular space by instrumentation, usually due to a pressure differential between the outside world and inside blood vessels. If the air embolus is large enough, it can lead to a dangerous occlusion of these blood vessels.

There are two types of gas emboli: venous and arterial3. Venous gas emboli are most often caused by with the insertion or removal central venous catheters3. Arterial gas emboli are commonly caused by angiography, which introduces a catheter directly into arterial flow, or by congenital heart defects that allow for intermixing of venous and arterial blood3. The symptoms of a gas embolus are nonspecific: shortness of breath, chest pain, coughing, altered mental status and dermatological findings3. During surgery, however, patients are often under anesthesia and cannot demonstrate these clinical signs3. In patients undergoing procedures with anesthesia, decreased end-tide O2 is the earliest sign of respiratory compromise from gas embolism, while decreased oxygen saturation from pulse oximetry is considered a late sign3. A large amount of air is required to cause a clinically significant occlusion in venous circulation, however arterial compromise can be the result of very small air bubbles3. For this reason, exceptional care must be taken in patients with an anomalous connection between the left and right heart, such as those with a patent foramen ovale or a septal defect3.

While the most common causes of gas emboli include central lines and arteriography, there is a high incidence of venous air emboli in patients who have recently undergone neurosurgery2. The quoted incidence in the literature is anywhere between 16-86%, though most of these events do not result in patient morbidity or mortality2. While there’s no consensus on gas embolism-related mortality in neurosurgery, there are certain procedures that seem to increase that risk2. For example, neurosurgical procedures that have the patient in the seated or semi-seated position seem to be associated with a higher risk of venous air embolism, which is one of the reasons why this positioning has become less popular in the US2. Other high-risk procedures include deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease, stereotactic surgery, and craniosynostosis correction1,2.

Treatment of venous air embolism consists of supplementing volume status and oxygenating the patient with 100% O2 via a non-rebreather mask3. The patient should be placed in left lateral decubitus positioning to encourage air bubbles to travel into the right atrium instead of getting stuck in the right ventricular outflow tract3. In cases of cardiac arrest, cardio-pulmonary resuscitation should be initiated quickly to maintain organ perfusion, and escalation of therapy including ICU-level care, ECMO or hyperbaric oxygen therapy should be considered3.

Although a rare occurrence, gas embolism can be a dangerous and sometimes fatal complication of surgery and invasive procedures. Extra precautions must be taken during certain procedures, particularly ones requiring endovascular instrumentation, to mitigate this risk and optimize outcomes.

References

- Faberowski LW, Black S, Mickle JP. Incidence of Venous Air Embolism During Craniectomy for Craniosynostosis Repair. Anesthesiology 2000; 92:20 doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/00000542-200001000-00009

- Giraldo M, Lopera LM, Arango M. Venous air embolism in neurosurgery. Colombian Journal of Anesthesiology 2015; 43(1): 40-44. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcae.2014.07.002

- McCarthy CJ, Behravesh S, Naidu SG, Oklu R. Air Embolism: Practical Tips for Prevention and Treatment. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2016; 5(11): 93. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm5110093